Why are players so much better after they leave Manchester United?

Some say that Manchester United have accidentally become football’s leading glow-up clinic. Leave Old Trafford, change your surroundings, and suddenly the lighting is better, the confidence is back, and everyone is asking why you didn’t always look like this.

Players leave Old Trafford and suddenly look freer, sharper, and more decisive. Scott McTominay went from a rotational midfielder at United to a Serie A title winner with Napoli and finished 18th in the 2025 Ballon d’Or rankings. Antony struggled for rhythm and confidence in England, then became a productive wide forward at Real Betis. Álvaro Carreras left the club quietly and ended up earning a major move to Real Madrid. Ángel Di María lasted one unhappy season in Manchester and immediately returned to elite output elsewhere.

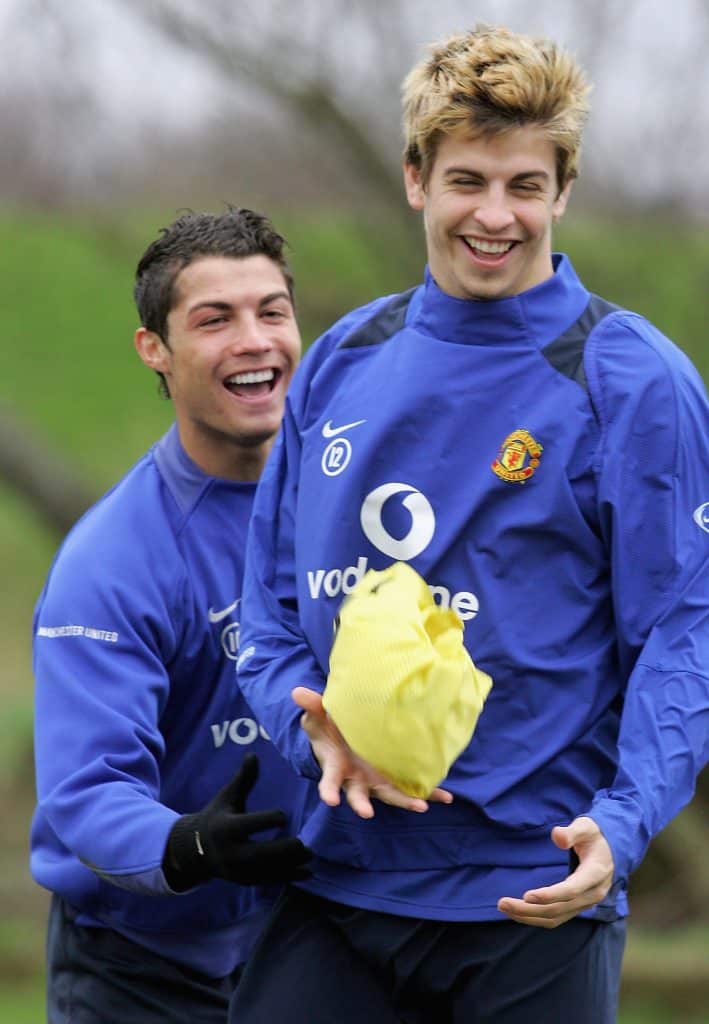

The list keeps growing. Memphis Depay rebuilt his career in France and Spain. Angel Gomes matured into a senior international midfielder. Gerard Piqué became one of the defining centre-backs of his era. Anthony Elanga turned from squad depth into a Premier League difference-maker.

The perception now feels baked in: players leave Manchester United and get better.

That perception is not entirely fair. It is also not entirely wrong.

Are Manchester United really ruining talent… or is it myth?

Scott McTominay and the making of a champion

At Manchester United, Scott McTominay played 255 senior matches across all competitions. He scored 29 goals, often in bursts, and was rarely trusted as a first-choice midfielder in possession-heavy games. Across his final three league seasons at United, he averaged fewer than 20 starts per season, frequently used as a late runner or emergency defensive presence rather than a tactical focal point.

At Napoli, the framing changed immediately. In his first Serie A season, McTominay scored double-digit league goals, most of them from open play, arriving late into the box rather than standing as a static midfielder. He played more minutes in a defined role in one season than he had across several at United, and Napoli won the league with him as a core contributor. He came 18th in the Ballon d’Or rankings and won Serie A Player of the Season.

The footballer did not change. The role did.

At United, McTominay was a solution to problems. At Napoli, he was part of the plan.

But, in United’s defense, when McTominay was asked directly by CBS Sports about that “post-Manchester United effect”, he didn’t lean into the easy storyline, as other players have done, but rather he basically swatted it away. He called it a myth and “too easy of an excuse”, stressing that United actually gave him everything he needed (training, nutrition, tactical work) and that what really changes after a move is confidence and minutes, not some mystical Old Trafford curse.

In other words: he isn’t presenting himself as a player who was saved by leaving; he’s saying the player was always there, and the difference is rhythm, belief, and being trusted week-to-week. An example of a serious leader.

Scott McTominay jumps higher than CR7 with his heroic goal for Scotland in the World Cup Qualifiers!

— 365Scores (@365Scores) November 20, 2025

The Napoli midfielder has earned Ballon d’Or shouts for his acrobatic finish. pic.twitter.com/bTKexFJ0O2

Antony and what confidence actually looks like on the pitch

Antony’s Manchester United numbers were stark for a player signed to be a primary attacking outlet. Across two and a half Premier League seasons, he scored five league goals, averaged under one shot on target per game, and completed fewer successful take-ons than most starting wingers in the division. His body language often mirrored the data: hesitant, predictable, conservative.

At Real Betis, his output spiked almost immediately. In his first half-season in Spain, he recorded more goal involvements than he managed in his final 18 months at United, doubled his shot volume per 90 minutes, and completed take-ons at a far higher rate. He attempted more progressive carries per game and received the ball higher up the pitch, closer to the box.

At Betis, Antony had a stable role, a full-back overlapping consistently, and a system designed to isolate him one-on-one. At United, he was often tasked with both providing width and compensating for structural gaps behind him. That burden showed.

Antony has scored more goals for Betis than he had for Man Utd in MUCH LESS games. Any explanation for that? 🤔 pic.twitter.com/EWX9uSejCo

— 365Scores (@365Scores) November 5, 2025

Álvaro Carreras and the cost of developmental congestion

Álvaro Carreras never failed at Manchester United. He simply never played.

Between 2022 and 2023, Carreras made no senior appearances, spending most of his time in the academy and on loan. He was blocked by senior full-backs and a squad built for immediate pressure rather than long-term growth.

At Benfica, after a steal of a €6m move, Carreras became a regular starter. He logged over 40 appearances in a single season, ranked among the league’s most progressive full-backs for carries and chances created, and developed into a complete modern defender.

Real Madrid did not buy him on potential alone. They bought him after sustained top-level production.

🚨 OFFICIAL 🚨

— 365Scores (@365Scores) July 14, 2025

Real Madrid have confirmed the signing of Álvaro Carreras from Benfica, with an agreement in place until June 2031 ✍️

A long-term investment for the future — exciting times ahead for Los Blancos! 🔥 pic.twitter.com/UK4xAD6boP

Di María, Depay, Gomes, Piqué, Elanga: patterns, not coincidences

Ángel Di María’s United season is often reduced to vibes, but the numbers are revealing. In the Premier League, he scored three goals and registered ten assists, but his chance creation declined steadily as the season progressed, and he was increasingly used away from his preferred right-sided role. The moment he left, his production rebounded. At Paris Saint-Germain, he averaged double-digit assists per season across multiple campaigns and became a Champions League regular contributor.

Memphis Depay scored seven goals in 53 total appearances for United, often playing wide and receiving the ball far from goal. At Lyon, he averaged over 20 goal contributions per season, operating centrally with tactical freedom.

Angel Gomes made just ten senior appearances for United. At Lille, he became a consistent starter, posting strong progressive passing numbers and earning an England call-up.

Anthony Elanga averaged one league goal every 13 league appearances at United. At Nottingham Forest, he doubled his shot output, became one of the league’s most effective transition attackers, and regularly decided matches.

Gerard Piqué played 23 matches across all competitions at United. At Barcelona, he became a 600-game defender with multiple Champions League titles.

Manchester United’s environment magnifies underperformance

Manchester United do not judge players by contribution. They judge them by transformation.

A winger is not meant to stretch play. He is meant to fix the attack. A midfielder is not meant to support. He is meant to dominate. A defender is not meant to defend. He is meant to lead a rebuild.

That expectation, unfortunately for the players, distorts perception. A player who would be considered solid elsewhere becomes a symbol of decline at Old Trafford. When that player leaves and performs to a normal, sustainable level, it feels like a renaissance.

Tactical instability creates identity drift

Since 2013, Manchester United have cycled through multiple tactical identities: high pressing, deep blocks, possession football, counter-attacking, hybrid systems. Players are recruited for one vision and used in another.

This matters because elite footballers thrive on repetition. They need patterns, relationships, and predictability. Many of United’s departures improved simply because their new clubs knew exactly how they wanted to play and built around that idea.

Napoli knew what McTominay was. Betis knew what Antony needed. Benfica knew how to develop Carreras.

United have often asked players to figure it out as they go.

Ownership, noise, and constant evaluation

The last decade at United has been defined by churn. Executives change. Managers change. Recruitment strategies change. Public narratives swing weekly.

Players operate inside that chaos. When the environment feels unstable, players default to safety. They pass sideways. They avoid risk. They play to survive rather than to dominate.

When they leave, the relief is visible in their decision-making. They shoot earlier. They dribble again. They trust their instincts.

This is not softness. It is psychology.

Why the opposite stories rarely go viral

There is a selection bias at work.

When a player leaves United and struggles, it confirms nothing. When a player leaves and thrives, it confirms a story people already want to believe.

Paul Pogba’s post-United career has been inconsistent and interrupted. Jadon Sancho has not become a guaranteed elite winger elsewhere. Anthony Martial leaving does not ensure durability or dominance. Romelu Lukaku’s post-United career has included both prolific spells and public turbulence.

These examples exist, but they do not feed the myth. So they fade.

So what is actually happening?

Players are not magically improving when they leave Manchester United.

They are:

- Playing clearer roles

- Receiving consistent minutes

- Operating in stable systems

- Carrying less symbolic weight

- Being judged on performance rather than expectation

Manchester United’s scale turns normal development into failure and normal success elsewhere into transformation.

Until the club becomes boringly coherent again, the glow-ups will keep coming.

FAQs

Do most players actually improve after leaving Manchester United?

No. Some improve, some stay the same, some struggle. The successful cases are simply more visible.

Why does it feel unique to Manchester United?

Because United’s expectations, scrutiny, and instability magnify both underperformance and post-exit improvement.

Is this mainly a tactical issue?

Tactics are a major factor, especially role clarity, but psychology, pressure, and minutes matter just as much.

Are Manchester United bad at recruitment?

Not always. The bigger issue has often been fit, timing, and how players are used after arrival.

Can this narrative change for Manchester United?

Yes. Stable leadership, coherent recruitment, and consistent roles would significantly reduce the number of apparent glow-ups elsewhere.

By Nicky Helfgott – NickyHelfgott1 on X (Twitter)

Keep up with all the latest football news and Premier League news on 365Scores!